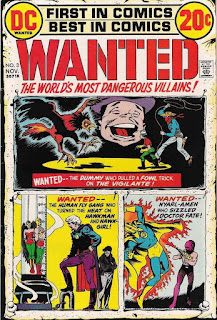

After reading Jennifer DeRoss's biography of Gardner Fox a few years ago, I was inspired to pick up The Golden Age Doctor Fate Archives. I was first introduced to the character in a reprint from Wanted: The World's Most Dangerous Villains #3, and I've read a few contemporary (well, they were contemporary in the 1980s and '90s) stories but I'd never dove deep into the character's background.

Doctor Fate debuted in More Fun Comics # 55 in the middle of 1940. Right out of the gate, he's described as a "student of ancient mysteries that were partially destroyed when Caesar burned Alexandria's library, delver in the unknown science of the occult and the weird, alchemist and physicist extraordinary..." Although he doesn't hesitate to use a right cross on his opponent, he's clearly a character more grounded in magic and mysticism. In his second appearance, he crosses the River Styx and speaks with the "Ruler of the Dead." In his third issue, he starts dropping Lovecraft-type incantations like "Nyeth thryalla" and "Fyorneth dignalleth." While the art by Howard Sherman doesn't hold a candle to the surreal landscapes that Steve Ditko would later use for Marvel's Dr. Strange stories, his style is better suited to a character like Doctor Fate than a more physical hero like Superman or Green Arrow.

But there's a couple pretty sudden shifts in the character. At the end of More Fun Comics #66, Doctor Fate -- who thus far had been a pretty mysterious figure -- surprisingly removes his helmet to reveal his secret identity to his lady friend, Inza. The following issue then provides a pretty vanilla origin story for the character. Then, in #72, Doctor Fate has, without explanation, begun wearing a helmet that does not cover his entire face. The character seems decidedly more mortal, succumbing to a simple gas attack, no longer uses any real mystical powers, preferring to smash through walls and wallop bad guys with his fists. In other words, where the original was a unique and clever approach to a superhero, this new iteration was largely indistinguishable from just about every other superhero around at the time. The change made no sense to me as it was the original creative team of Gardner Fox and Howard Sherman working on this the entire time... until I realized that Mort Weisinger took over from Whitney Ellsworth as editor with More Fun #71. Since there were no other changes to the team working on the stories and Weisinger has a reputation for being a somewhat dictatorial editor, it seems clear that Weisinger was the one who mandated the change, apparently not liking or approving of the mystical elements. (Although I'm unaware of any specific concerns or issues he may have had.) When Doctor Fate was brought back decades later, they fortunately returned to his mystical roots and largely ignored the later bland superheroics.

One curious thing that strikes me in the early issues is the lettering. While the initial stories have a fairly "normal" approach to lettering, some of the letterforms become hyperstylized by the fourth installment. Of particular interest are the "E"s and "F"s. Take a look at this splash page from More Fun #69. The center crossbar for each extends much further than either the upper or lower ones, making for a visually unbalanced letterform. It's almost distractingly hard to read in places.You really have to study Inza's dialogue in the lower left to understand what she's saying... even though it's only three words! Interestingly, The Comics Journal published a piece on Sherman a few years ago which includes scans of a handwritten letter to Jerry DeFuccio in 1984, and the "E" forms appear perfectly normal, suggesting the hyperstylized ones in the Doctor Fate stories were a deliberate affectation. Although I can't imagine why; typically, the middle bar is the shortest in font designs. Notably, this extended "E" practice effectively stops as soon as Weisinger takes over as editor.

I found a lot to like in the earliest Doctor Fate stories, and I'm disappointed almost all of the best elements were dropped so quickly. Before Weisinger turned him into yet another generic hero, the stories had some really clever and original ideas, and I would've preferred seeing more of that in the back two-thirds of that Archives volume. I can guarantee if that World's Most Dangerous Villains issue I first encountered included a reprint of a later Doctor Fate story, I would've dismissed it almost out of hand and promptly forgot about it.

Doctor Fate debuted in More Fun Comics # 55 in the middle of 1940. Right out of the gate, he's described as a "student of ancient mysteries that were partially destroyed when Caesar burned Alexandria's library, delver in the unknown science of the occult and the weird, alchemist and physicist extraordinary..." Although he doesn't hesitate to use a right cross on his opponent, he's clearly a character more grounded in magic and mysticism. In his second appearance, he crosses the River Styx and speaks with the "Ruler of the Dead." In his third issue, he starts dropping Lovecraft-type incantations like "Nyeth thryalla" and "Fyorneth dignalleth." While the art by Howard Sherman doesn't hold a candle to the surreal landscapes that Steve Ditko would later use for Marvel's Dr. Strange stories, his style is better suited to a character like Doctor Fate than a more physical hero like Superman or Green Arrow.

But there's a couple pretty sudden shifts in the character. At the end of More Fun Comics #66, Doctor Fate -- who thus far had been a pretty mysterious figure -- surprisingly removes his helmet to reveal his secret identity to his lady friend, Inza. The following issue then provides a pretty vanilla origin story for the character. Then, in #72, Doctor Fate has, without explanation, begun wearing a helmet that does not cover his entire face. The character seems decidedly more mortal, succumbing to a simple gas attack, no longer uses any real mystical powers, preferring to smash through walls and wallop bad guys with his fists. In other words, where the original was a unique and clever approach to a superhero, this new iteration was largely indistinguishable from just about every other superhero around at the time. The change made no sense to me as it was the original creative team of Gardner Fox and Howard Sherman working on this the entire time... until I realized that Mort Weisinger took over from Whitney Ellsworth as editor with More Fun #71. Since there were no other changes to the team working on the stories and Weisinger has a reputation for being a somewhat dictatorial editor, it seems clear that Weisinger was the one who mandated the change, apparently not liking or approving of the mystical elements. (Although I'm unaware of any specific concerns or issues he may have had.) When Doctor Fate was brought back decades later, they fortunately returned to his mystical roots and largely ignored the later bland superheroics.

One curious thing that strikes me in the early issues is the lettering. While the initial stories have a fairly "normal" approach to lettering, some of the letterforms become hyperstylized by the fourth installment. Of particular interest are the "E"s and "F"s. Take a look at this splash page from More Fun #69. The center crossbar for each extends much further than either the upper or lower ones, making for a visually unbalanced letterform. It's almost distractingly hard to read in places.You really have to study Inza's dialogue in the lower left to understand what she's saying... even though it's only three words! Interestingly, The Comics Journal published a piece on Sherman a few years ago which includes scans of a handwritten letter to Jerry DeFuccio in 1984, and the "E" forms appear perfectly normal, suggesting the hyperstylized ones in the Doctor Fate stories were a deliberate affectation. Although I can't imagine why; typically, the middle bar is the shortest in font designs. Notably, this extended "E" practice effectively stops as soon as Weisinger takes over as editor.

I found a lot to like in the earliest Doctor Fate stories, and I'm disappointed almost all of the best elements were dropped so quickly. Before Weisinger turned him into yet another generic hero, the stories had some really clever and original ideas, and I would've preferred seeing more of that in the back two-thirds of that Archives volume. I can guarantee if that World's Most Dangerous Villains issue I first encountered included a reprint of a later Doctor Fate story, I would've dismissed it almost out of hand and promptly forgot about it.