The problem we have, as mere mortals, is a lack of omniscience. We simply can't know anything beyond our immediate realm of experience. Even our learning from the experience of others is something that we have to undertake ourselves, whether by reading or listening or some other method of knowledge transfer. And even then, there's still the matter of interpretation -- the original experience is recounted to us in some manner by someone(s) who will invariably leave out some level of detail and we, in the process of absorbing the information, will process and filter it based on our own personal experiences. We cannot know, with any accuracy, what it's like to walk on the moon unless we actually go there ourselves.

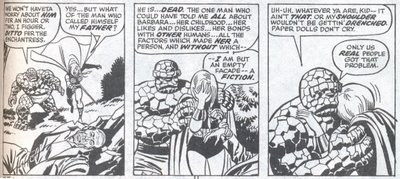

In comics, however, many characters are granted a level of omniscience that is impossible for us to truly fathom. There's a certainty in Ignatz's or Sluggo's or She-Hulk's knowledge that they are, at the end of the day, drawings on a piece of paper. We don't have that luxury. For as much as you may know that God exists or doesn't, your certainty in that "fact" is just an act of faith. We don't have the actual knowledge because our creator/s (if indeed we even have them in the larger context -- I'm not talking about your parents here) have not imbued us with it in the way Windsor McCay might have done with Little Nemo. The act of creating a character -- a paper doll to pick up on Roeg's metaphor -- gives the creator the right to implant as much or as little knowledge into him/her as is appropriate. Reed Richards is a genius because Stan Lee said he was. Dr. Manhattan was omniscient because Alan Moore wanted him to be.

This, of course, can lead to what is considered bad writing. Can you imagine the uproar among fans if, for example, Commissioner Gordon asked Batman about how Alfred the butler was doing? The relationship between Batman and Alfred is one that Gordon should have no knowledge of because his character has never been given that information within the context of continuity. But a writer, being the unseen force behind that exchange, does have omniscience of that world and can give that specialized piece of knowledge to any character at any time. It wouldn't make sense within how the story is presented, in all likelihood, but it's still the creator's prerogative.

Of course, there's the rub. For any story that presents free will and/or existentialism as "correct" the characters in the story are following a prescribed destiny. For any knowledge that a character might possess about the nature of free will -- for that matter, any knowledge the character possesses at all -- they are inherently bound by the will of their creator(s). The paper dolls simply cannot exist, much less have any meaning, without someone to create them. You can say Kang chose to defy Destiny itself in Avengers Forever but Kang really didn't have any say in the matter; his course of actions were laid down by writers Kurt Busiek and Roger Stern. "All the world's a stage, and all the men and women merely players."

Where does that leave us? That free will simply cannot exist because nothing we humans create is capable of it? Of course not. As noted earlier, we humans are stuck with limitations that make us decidedly less than all-powerful. Once upon a time, we couldn't create apples that tasted like grapes, either, but look where we are now. Who's to say that creating independent, free will characters is that far off? Wasn't that part of the reason why Phineas Horton created the original Human Torch? Why Noonien Soong created Data? Why Sivasubramanian Chandrasegarampillai created HAL 9000?

(As a curious aside, all those characters I just cited were used, in part, to explore the very notion of self. Is a being's own quest for life's meaning sufficient to consider it "alive"? Is life and a sense of self strictly limited to biological organisms? Does the origin of one's existence truly impact whether or not one can have free will?)

Man's quest for life's meaning is, for all intents and purposes, perpetual. Every day, we wake up and try to muddle our way through life, acting on a nearly infinite number of judgment calls. The next day, we do the same thing. Comics -- and, indeed, any media -- can show us possible alternatives that other people have considered; they can pass along messages about what other people think life means. They can go so far as to give us a taste of omniscience, seeing events through the eyes of any number of characters. But, again, the ultimate irony of the situation is that the very mouthpieces that we see as proponents of self-direction and choice are they themselves shackled to the will of others.

1 comments:

This question, I hold, is the proper arena for Pascal's Wager.

Pascal's Wager doesn't make a lot of sense when it comes to the question of God's existence, for these reasons:

1. If we "choose" to "believe" in God just because of the reasoning of Pascal's Wager, God would certainly see through that, and would likely not count it as actual belief.

2. The decision to believe in God has actual real-world consequences, assuming one acts in accordance with one's stated beliefs, which may or may not be beneficial, and so it's not the no-lose situation that Pascal says it is (although, to be sure, in his time, there were possibly very serious consequences to public nonbelief, so his math might come out differently from how it does for us).

But if you apply it to the question of free will, you get different results:

1. Free will, as an abstract concept, doesn't care if you choose to believe in it or not, so that aspect of the question can be taken off the table.

2. If there is such a thing as free will, but you think and act as if there isn't, you may run into trouble. It may lead you to make poor decisions.

3. If there isn't a such thing as free will, but you think and act as though there is... well, the part of this sentence before the ellipsis is meaningless. If there isn't a such thing as free will, you think and act however you were going to think and act anyway and there's nothing more to be said about it.

Post a Comment