Let's go back to an era when you could only get comics from a newsstand. The guy running the newsstand was getting hundreds of periodicals on a continual basis, almost all of which were running on different schedules. Some came in daily, some weekly, some monthly, some bi-monthly, some quarterly... In the days before computers, this would be an incredible amount of work to keep track of what came in when. And it was important to keep track of that because most periodicals were sold to retailers on a returnable basis. That is, if the retailer didn't sell everything he ordered in a given timeframe, he could return them to his distributor for a refund.

Naturally, though, this wasn't a

completely open-ended arrangement. You couldn't return something, for example, a year after it was published and expect anything back. You had a window of maybe a couple of months at most, depending on the frequency of the periodical.

Now you'd think that since most periodicals post their publication date on the cover, this wouldn't be an issue. The December 15th issue of the

New York Times came out on December 15, right? With magazines and comics, though, publishers frequently tried to look more current than they actually were. So they'd print a date somewhat later than when the book actually went on sale; a book that was actually published in January would have a February date and would (theoretically) look

more current than the other magazines next to it with the actual date.

(This got out of hand eventually, and you'd have comics' publication dates off by 6-8 months!)

So to keep track of when comics ACTUALLY hit the newsstands, retailers would literally write the date it came out right on the cover. Here's a copy of

Fantastic Four #1. It's cover dated Novemeber 1961, but you can see the "8/9" clearly written under the "R" in the title, indicating it really hit the stands on August 9th.

(Note that local distribution channels worked on slightly different schedules, so not every issue of

FF #1 across the country came out on August 9. Some could easily be hand-dated a week in either direction. In fact, I've seen copies of

FF #1 dated as early as July 30 and as late as August 21!)

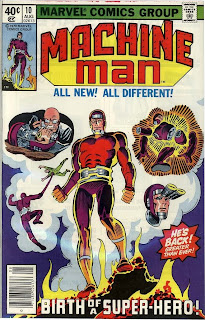

Writing on each and every issue was a bit tedious, though, and retailers no doubt complained to their local distributors. What many of the regional distributors started doing was slapping a bit of paint across the top edge of the comic. So, now, instead of having to make note of the actual date, the distributors could just say, "We're accepting returns on all red-coded books." As they'd change the color with each shipment, it became easy for a retailer to just scan through his inventory and pull out any comics that had a bit of red (or whatever the color was for that week) on the top. Take a look at the top of this

Machine Man #10 where you can see a bit of red splotching above the "Marvel Comics Group" banner.

Now, this wasn't done at every distributor, so it's not universal. And since it was done at the regional level, there's no consistency in color or the... ah... delicacy of application. So you can find some issues with what's called "overspray" when the person who was actually putting the color on the books was perhaps a bit too generous, like with this copy of

Astonishing Tales #5...

This system lasted for about 10-12 years, primarily through the 1970s. As comics became more and more collectible, and with the emergence of the direct market, this was clearly unacceptable to readers. The publishers themselves then began color-coding their own books, so the regional distributors wouldn't have to. But, so as not to put an ugly color bar on their covers, which they viewed as a primary sales tool, the color bars were put on all the interior pages. But by running them at the very edge of every page, a retailer could still make out the colors without having to open each book.

Keep in mind that this was all done because comics were being sold on a returnable basis at least in some meaningful capacity. These color codes weren't really being used by the direct market because their books weren't returnable in the first place, but they still had to deal with the overspray and color bars because the books still came through the same channels. Once the direct market became, for all practical purposes, the only real way for individual customers to purchase comics, this color coding system was no longer necessary. This color system was only being used to tell retailers when they could return the books; with the non-returnable set-up of the direct market, this was a non-issue. Publishers eventually dropped the color bars entirely since effectively none of their books were getting returned anyway.

Not coincidentally, I expect, the color bars ceased around the same time when publishers began emphasizing the collectibility aspect of their books with foil, die-cuts, embossing, and the like. It was part of a general realization that their comics were no longer going to a mass audience, but almost exclusively to people who were collecting them. But that's another set of issues entirely!

3 comments:

I never would have guessed that this was the explanation.

How much would a Feb03 Batman #608/609 with the color barcode printed on the top of the comic and on the top throughout the book cost? At the time I saw this in 03, this was the only Batman 608/609 with a barcode among the rest that didn’t. Wondering if I shouldn’t have passed on it...

The color bars and bar codes don't really have any impact on price. It's just not something collectors seem to care much about, one way or another.

Post a Comment